Good morning subscribers, happy Monday (these subscriber-only posts usually go out on the weekends, but sometimes they go out on Monday, and sometimes they go out on a different day entirely. It’s fine). This is a weird sort-of-essay that started out as a piece of something I’m writing for tomorrow. What was supposed to be one tangential paragraph about New Year’s Eve in that essay kept mutating and expanding and turned into its own thing. It doesn’t really make any kind of defensible sense to publish an essay about New Year’s at the end of February, but I like this enough to want to do something with it, so I’ve made it into a subscriber-only post. I guess it’s another kind of b-side. enjoy.

before that, though, a quick reminder that yearly griefbacon subscriptions are on sale for just two more days (today and tomorrow), until the end of the month (11:59 on Tuesday, which also happens to be my birthday). If you got here through a forward and you enjoyed this and would like to support this project and read more, if you’re reading the preview and would like to upgrade your subscription so you can read all the paywalled posts (lots! so many!), or if you know someone who would like to subscribe but hasn’t been able to afford the full price, now’s a great time to subscribe at a discount.

In deep summer in 2020, when it seemed we were down in the rock bottom of whatever we had all lived in up until then, my husband and I declared a new year. The previous few months had felt so long, a century dragging from February to July. It seemed that surely a new world must be coming out of the wreckage of this one; surely things couldn’t get this bad without it yielding, sooner than later, some spectacular rebirth. But that never happened. The city cleared out and the cops enforced curfews and every day somebody else got sick, numbers piling up until they fell off the page. All the wrong things survived and all the wrong things disappeared. It all just kept going on, no rewards and no visible horizon.

On a particularly bad afternoon that now blends in my mind with every other particularly bad afternoon that summer, Thomas, fed up with it, made collard greens and black-eyed peas for dinner and declared it a new year. We can have a new year whenever we want, he said. Fuck this year, let’s start it over right now. He chilled sparkling cider, standing in for champagne, in an ice bucket, and we sat out on our absent neighbor’s back deck in the sweltering late-afternoon of an abandoned city, and toasted to the new year.

It didn’t work, which is to say it worked as much as any of the other new years do. It did nothing, and we believed in it for a second, and then the next day was the same as the previous one. If we did make changes, we made them ourselves, based on an animating fiction. Nothing happened to us. The summer we lived in the next day was still the same summer. You can have a new year whenever you want, and it will change your reality from one day to the next just as much as it does from December to January. Begin as you mean to go on, say the British, and maybe we did, on that wet afternoon, in that empty summer, when we dressed up for no reason and made a bunch of arm-swinging, anxious promises.

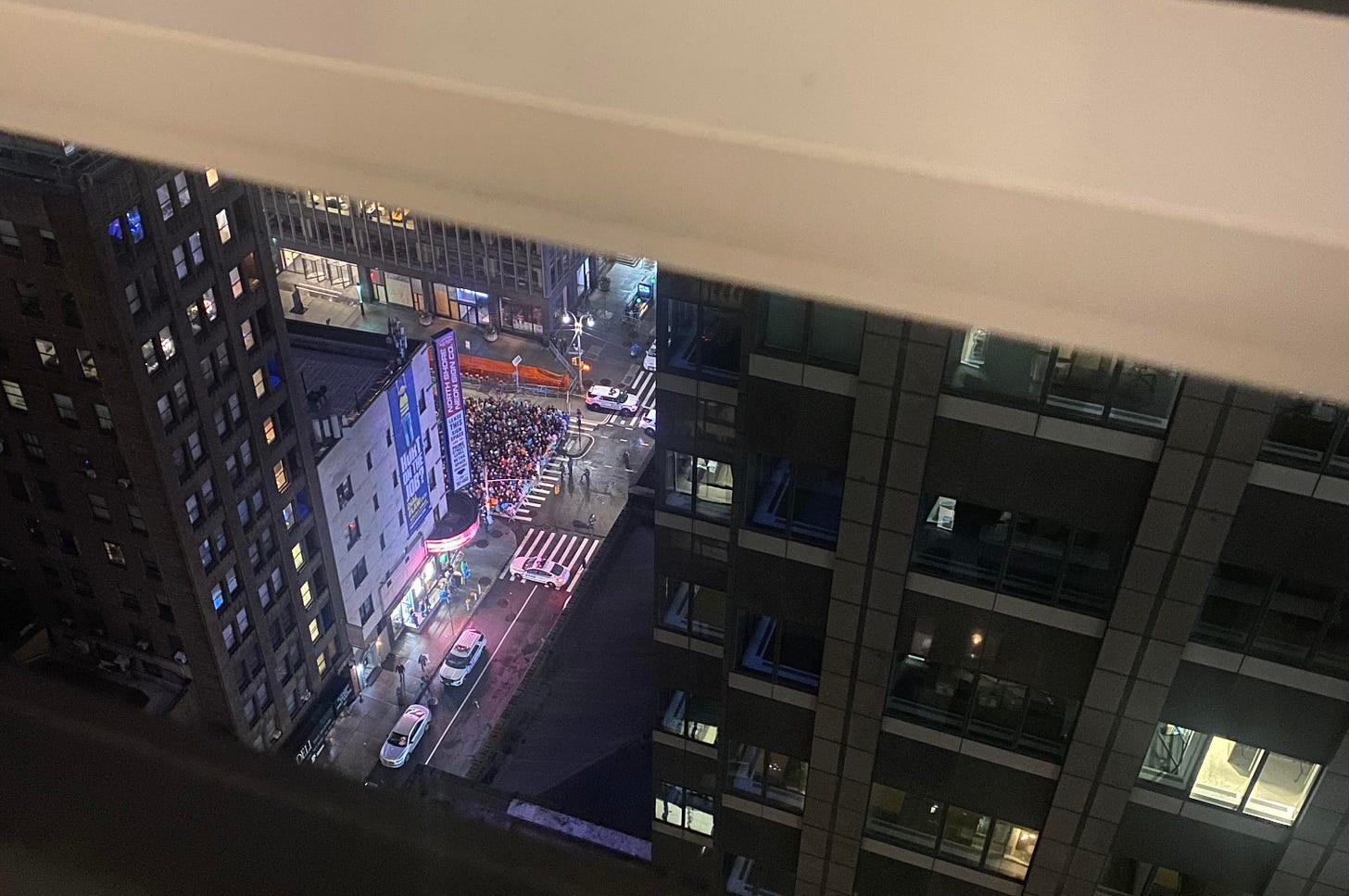

The official New Year’s holiday that bisects the winter calendar is no different from that summer afternoon. On the last day of December this year, Aaron invited Thomas and I over for New Year’s. We couldn’t tell if it was a party or just the three of us, and didn’t want to ask, and when it turned out it was just the three of us we were still never sure, any of us, whether or not it was a party. But it was New Year’s, so probably it was. We didn’t want to go out on New Year’s, the worst night of the whole year to leave your apartment, but we did, because we were doing the same thing we’d done on that summer day, trying to believe a new thing into existence, trying to make something out of nothing.

Every party, in its own way, declares a new year. A party declares that what this night means is within my control and not beyond it. Rituals are an illusion of control, but so is everything, from religion to computers, all up and down the living and evasive world. One New Year winds up and goes on and flames out and then there’s another. On the last day of December I went to a party because I was afraid I had forgotten how to go to parties; I went to see a friend because I was afraid I’d forgotten how to be a good friend. I was afraid that the things everyone had told me about how wild love dulls and decays as we age were true. I wanted to prove something wrong, which is also the impulse behind every new year, behind every ritual that starts anything over, from an anonymous circle of chairs in a basement to a high-church Easter service. I’ll show them this time; I’ll show them. I went to a party to try to get control of the year, to try to wrest its meaning into my own hands.