everything I've watched in however long it's been since the last one of these, part one

featuring several unfair jokes and several genuine recommendations

hi everyone. As subscribers already know, I had a week last week that involved emergency surgery for one of my cats (she’s fine now, everyone’s fine, our local vet is great, nothing turned out to be a big deal, but I cannot honestly recommend this as an experience) and I fell behind on pretty much everything, including last week’s essay. As a result, I’ve been working on another installment of “everything I’ve watched in the last however long” for over two weeks now, and it’s gotten way too large for a single post. So, I’m sending one piece of it now for everybody, another piece only for paid subscribers tomorrow (here’s where you can subscribe to make sure you can read it), and the last couple pieces next week. For now, here’s part one of a bunch of thoughts on everything I’ve watched in the last however long. (Here are some other installments in this series, if you feel like reading more of this sort of thing.)

Top Gun: Maverick: People sometimes call Top Gun: Maverick a dad movie, but that’s wrong. Tom Cruise is a man in his 60s, a father to several actual children, and a relic of the 1980s, but he isn’t a dad. Dads are resigned. Dads are a wine bar, dads are a book about a dead president, dads are a Sunday night. Dads are the luxurious comfort of failure, the softest part of the couch, and a story about what could have been. Dads are when the whole karaoke bar sings “Piano Man.” Dads are a slow jam, a minor key, a basketball game where your team is losing but they tried their best. Dads are tired, and Tom Cruise has never been tired once in his life.

Dads are a rock song in which the lead singer apologizes for something; dads are a song that sounds like a love song but is actually about getting killed by the mafia and it’s your own fault for not making better choices in your life. Dads are the way that when a professional athlete retires and becomes a commentator on the same game he used to play, his suits never quite fit him right. Dads are a Volvo driving ten to fifteen miles over the speed limit but not more than that. Dads are the way that caring for other people often means allowing yourself to be the butt of the joke; when someone succeeds at applying this principle, that’s about dads, and when someone fails at it, that’s about dads, too. Love is being the fall guy, and so is being a dad.

Tom Cruise isn’t a dad. Tom Cruise is a credit card. Tom Cruise is test-driving a car that’s too fast and too expensive for you; Tom Cruise is when the car rental place sells out of normal cars and gives you a red Mustang convertible because it’s the only thing that’s left and then you realize that a Mustang convertible is a terrible car to actually drive. Tom Cruise is an instagram filter; Tom Cruise is when somebody brought coke to the party. Tom Cruise is that feeling I would sometimes get last summer when I would go out early in the morning and play basketball and then walk across the park to do a whole different workout and afterwards I’d walk back home with my giant water bottle and feel like I’d done it, I’d finally passed the Presidential Physical Fitness test. Tom Cruise is the President Physical Fitness test.

A dad is a steakhouse where the prices haven’t changed since the 1980s; Tom Cruise is an expensive restaurant with mediocre food on the 60th floor of a skyscraper. Tom Cruise is what I imagine it must be like to be someone who isn’t scared of flying. Tom Cruise is the idea that war is noble, and something that can be decisively won. Dads exist in proximity to all of these things, but their relationship to them is fundamentally different, a song transposed into a minor key, the sadness behind the joke. Tom Cruise has never told a joke in his life.

Anyway, I thought Maverick was fine; I probably would have liked it better if I’d seen it on a big screen. Jennifer Connolly makes me want to get botox the way seeing a pizza in a TV show makes me want to order a pizza.

Poker Face: Natasha Lyonne is the Beowulf of not being like other girls. There was this thing in the aughts where the coolest and sexiest thing a woman could do was be as much like a man in his 80s as possible. To be sexy, we were told, you should aim to be your own grandfather, but in the body of an underwear model. Maybe that’s why the way in which Poker Face felt retro to me was less about the 1970s, and more about 2007. I enjoyed it, but there’s such a huge “I’m only friends with guys, they’re just so much more chill” stink on this and, in a way I can’t quite defend coherently but which I feel strongly is true, on all recent Rian Johnson properties. “Columbo but it’s a lady” is the girl who only drinks whiskey of TV pitches, even if it’s great to see a woman in her forties be the ostensibly cool and sexy lead of an ostensibly cool and sexy TV show without her having to be a lawyer or have clean hair.

But then again, I love this shit; I came of age in the heart of the “not like other girls” era and, like a coffee stain on a cream-colored rug, I’ll never quite get it off me. I wish Poker Face had more teeth, and I wish it weren’t so cute, but I wish that about pretty much everything lately. That’s the problem with television, and with the way in which everything is television now, the monkey’s-paw bargain of the stupid little golden age of television we got fifteen years ago, which, on balance, probably wasn’t worth it. I do love to see my actual mother Cherry Jones get a meaty part and a nice paycheck, though.

Elvis: There’s this one scene in Pawel Pawlikowski’s Cold War (2018), in which a bunch of people, all of whom have recently lived through World War II in variously traumatic ways, are gathered in a late-night dive in Paris. It’s 1955, and what happens next is that Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock” comes on, and every character younger than thirty, or maybe even twenty-five, loses their entire shit. Young people jump up on tables, and scream, and dance with flailing, bacchanalian abandon, so close to the music that no light passes between it and themselves. Meanwhile, every character over the age of thirty stays seated, with no idea what’s happening, and why, and why it is that they can’t feel it. In the first three notes of a song on a radio, the world is transformed, but that transformed world is one only young people can enter. The second half of the twentieth century starts here, in a fat-fingered guitar chord that slashes across the room like a knife opening a letter. The page breaks, and the old truth falls away. The new one arrives with its short skirt hiked above its knees and its wet mouth hungry.

This isn’t an Elvis song. Haley’s hit just barely predates Elvis’s breakout moment, but it sounds like Elvis to me because I know what happens next. Watching this scene in this movie was the first time I ever felt like I understood Elvis, despite having heard plenty of Elvis’s music before. That frenzy, so non-native to the self-consciously old-fashioned, broody European wartime black-and-white vernacular in which the rest of Cold War takes place, was Elvis, even if the song technically wasn’t.

I’d never liked that Haley song, and I still don’t; l’d never really gotten Elvis, and I still don’t, not really. From almost a century on, that era’s youth culture has always seemed impenetrable to me, what it supposedly meant then utterly at odds with what it sounds like today. I’ve listened to Elvis’s songs, and watched archival footage of his performances. I’ve read accounts of the swooning sexual hysterics into which this strange, princely boy, in his high-camp eyeliner and his shoe-polish hair, sent teenage audiences. I know that parents barred their daughters from attending his concerts, and American television broadcast his early performances only from the waist up. But hearing an Elvis song has always been like trying on a dress that belonged to my grandmother.

Watching this scene, though, the music felt sweat-drenched and sticky-bodied, like all the lights coming on in a room. It was flesh insisting its way out of clothes and the neighbors across the street leaving the shades up and the lights on while they fuck. For once I could understand more than academically that Elvis changed culture in a way more comparable to the advent of free porn on the internet than to Dylan plugging in his guitar at Newport. For one minute and fifty-one seconds, I could reach out my hand to join an unbroken line back down nearly a hundred years, and get a jolt of the same electric current that my grandparents might have felt when they were young, before my parents were born, before the rest of the twentieth century happened to them.

Anyway, I haven’t seen Elvis. I did rewatch Strictly Ballroom recently, though, and I recommend that deeply stupid movie so much.

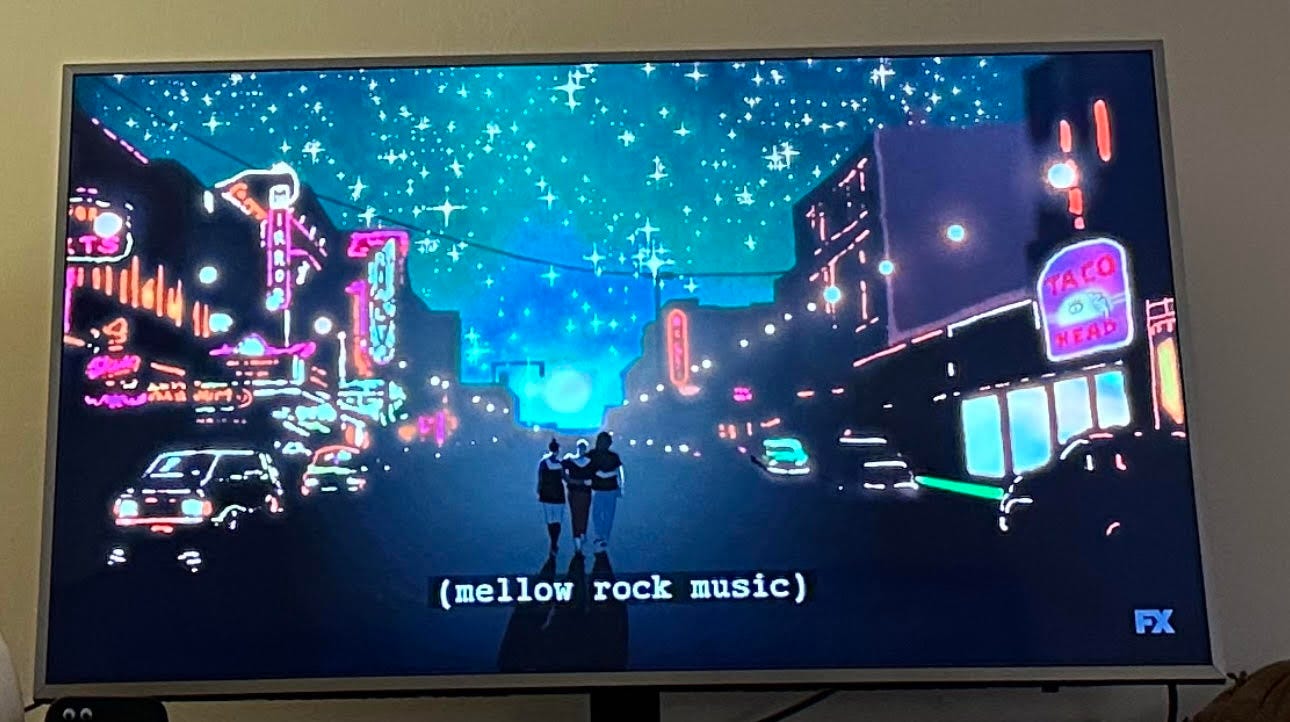

My Year of Dicks: I watched this movie because, like a lot of people, I thought the title was funny, and then I found myself enormously moved and in the embarrassing position of desperately wanting a movie to win an Oscar (it didn’t).

My Year of Dicks is twenty-four minutes of whimsically hand-drawn animation that’s also the best high-school coming of age movie in at least a decade. I didn’t have a good time in high school, enough that I tend to avoid this kind of movie. Stories like this one — teenagers learning to navigate love and sex and romance in the gentle incubator of a small town high school friend group—- usually annoy me, but this one didn’t. Maybe one of the gifts of getting older is that youth becomes more and more fictional as it recedes further away. The made-up idea of adolescence that no one really had begins, at a distance, to include all of us who were ever young at all. I loved this movie, and it had nothing to do with me; the fact that it resonated with me is laughable, and yet it did. Perhaps that’s the deceptive nature of memory, the boat cast far enough off from the shore that the shape it makes on the horizon could be just about anything.

Or maybe it’s simply that this is a really great movie. The animation is cute and smart and lo-fi in a way that made me miss the 90s, a decade during which I wasn’t a teenager and of which I have barely any memories that would induce the nostalgia I somehow manage to feel for it anyway. Maybe it’s that creator Pamela Ribon started out as a Television Without Pity recapper, and that version of the internet sometimes feels like a college that all of us who came up on it went to together. Whatever it is, this movie is great, with beautiful, witty visuals and killer jokes, and you should take twenty-four minutes out of your day and watch it.

The Ninety-Fifth Academy Awards: Had I been ten or twelve years old in the spring of 2020, I might have believed for years afterward that my parents were deeply committed amateur bread-bakers. I might have understood them, for the rest of my life or at least for the next decade, as people obsessed with cooking elaborate dishes from scratch, delivering meals to neighbors, and doing meticulous, obsessive home craft projects. There are kids in middle school right now who will probably get all the way into adulthood telling the new people they meet in college and at their first jobs, at tables in the back of bars and at sweaty house parties, in the friend groups that they’ll steal from the boyfriends they’ll break up with, that their parents loved to binge-watch old television and play games on their phones, and that whatever desperate, awkward habits their parents put in place to get through those bizarre couple years were permanent parts of their family’s personality, rather than scrambling happenstance solutions.

My parents and I moved west across the country around the time I started kindergarten. It was the 1990s, and California was still Hollywood. The company town was still Los Angeles, but the long arm of the magic of the movies spread all the way up Highway One into the green foggy hills along the Bay. People who had made their millions in the company town bought fuck-off homes high among the redwoods, and stained the movies all over the rest of the coast, while down in the foothills, former flower children were quietly inventing the internet and the end of this version of the world.

But we didn’t know that yet. My parents had put their stakes down in the land of the movies, so they pretended to care about what everybody else cared about. They learned to speak the language of the movies not because they loved the movies, but because they were determined make a home in the place where we now lived, to train themselves to grow in the landscape where they’d been planted. As a kid, I thought things like Spielberg and Star Wars were things my parents had always loved. I only figured out much later that the movies were just a form of small talk that they had had to learn.

My point here is that my parents never really cared about the Oscars, but I didn’t know that until well into adulthood. I believed for a long time that they deeply and obsessively loved movies, and awards shows, and celebrities in outfits. I can see now that they didn’t particularly care about any of that, because almost no one does. Awards shows, and the Oscars in particular, like other big-budget Sunday night television, are about how we all just want something else to do. We want something to happen that’s big enough that we can’t hear the inside of our own minds over it for a couple hours.

Anything can get its hooks in you if it shows up at the right time. Once a year, starting in the mid-afternoon, my parents and I would get a pizza and settle in on the old couch in front of the TV in the kitchen. We’d make predictions based on nothing, and get really invested in the competition amongst a bunch of movies none of us had seen, and in the sartorial choices of a bunch of people none of us had ever met. I remember that we did this every year, but it’s more likely we only ever did it once or twice, and it’s possible it never happened this way at all. My adult relationship with my parents often involves me saying “oh of course you’re going to do this thing you always do,” or “oh of course you love this thing you’ve always loved,” only to have them look at me like I’ve suddenly grown three extra heads.

But that particular ritual, even if it only occurred once or twice, happened to coincide with the most impressionable years of my childhood. I folded it up into my understanding of what it meant to be a person. Awards shows are silly and embarrassing and I’ve seen fewer than half of the movies that were nominated. But two Sundays ago, my husband and I ordered a pizza, and cleaned up the living room, and poured ourselves drinks in nice heavy glasses, and sat down on the couch to watch the Oscars. I got to pretend, for a few long hours of a deeply boring television broadcast, that I was a real person, that I’d managed to do it, that I had built myself a home in the world, just like everybody else.

WIDOWS: My phone automatically puts the title of Steve McQueen’s criminally underseen 2018 heist movie in capslock and that’s kind of all you need to know. Have you seen Widows yet? No? Go watch Widows immediately, it’s a rainy Saturday afternoon, just put on Widows right now.

thanks so much for reading. this is griefbacon’s weekly public post. if you enjoyed this and want to read more, maybe consider upgrading to a paid subscription? there’s lots more content and some of it is a lot like this and some of it is much weirder. the next installment of this round-up is coming tomorrow, just for paying subscribers. eventually one of these is going to be just a list of what perfume every character in Tár wears, and that’ll for sure only be for paying subscribers, so if you’re one of the five to seven people for whom that’s an enticement, come on and sign up now.

Sooo interesting to hear your take on Poker Face! Oddly I thought it was the other way around, in terms of the only friends with guys things, I thought her female friendships were wonderful especially with the female trucker. I totally agree about the whisky/beer drinking thing although I thought it legitimately worked here - it often feels very forced when it’s a male cop for example. The bit that annoyed me the most was the way that the whole chasing-a-fugitive narrative just totally disappeared for whole episodes at a time. I get the “vignette” nature or “anthology” thing that they were going for but I thought the original hook of the first 2 episodes was so strong, I didn’t understand why they let it slide. Also some episodes totally disappeared up their own ass for long stretches. But overall I thought it was incredible. And HER HAIR! Me and my husband were trying to come up with theories of how they managed to get it to look like that! Just amazing.

¨I’d finally passed the Presidential Physical Fitness test. Tom Cruise is the President Physical Fitness test.¨

Good God, I´d forgotten about that thing. (At some point I checked myself out on it, did fine, and then blew it off. Yay.)

At any rate, I never saw the first Top Gun... no point in seeing the second. I have failed America in that way and I am totally at peace with it.

¨That’s the problem with television, and with the way in which everything is television now, the monkey’s-paw bargain of the stupid little golden age of television we got fifteen years ago, which, on balance, probably wasn’t worth it.¨

We live in the land of commercial now, so all the commercials are out here trying to do Awkward Dada and Mugging for Surrealism. I can´t say this has been an improvement.

¨I’d never liked that Haley song, and I still don’t; l’d never really gotten Elvis, and I still don’t, not really.¨

Same. Or rather, I get it enough to not care. It´s Black Music for White People - given that it originates smack dab in the middle of the spasmodic end of Jim Crow. It made a certain kind of white person very angry and that worked well enough that the Wonder Bread substitute for biscuits (no chitlins, beans or collard greens, please, we´re white) sold like, uh, hotcakes.

[Seriously: BB King, 1951: https://youtu.be/uUWLXeGIDSo - blues/R&B - basically proto-Zeppelin or proto-Cream

Fats Domino 1955: https://youtu.be/uLvXVnpnR84 - practically big band for the blues with stop time!

And Chuck Berry, also 1955: https://youtu.be/npkoS9Q3QYk - a quickie ]

The young white ladies could lust after Elvis, natch. Not my thing, never understood it myself. BB King and that guitar, that I understand.

¨My point here is that my parents never really cared about the Oscars, but I didn’t know that until well into adulthood.¨

My mother, also a boomer, grew up right there in the middle 1950´s living across the street from a drive-in movie theater. So she got to listen to endless reruns of every crappy black & white monster movie they made in the 1950´s. As far a I can tell the result was she has ability to discern the differences between things. Black and white Japanese Samurai movies or the sountrack of the King & I, or Charles Aznavoir records, or early 00´s superhero movies, or an anime series about people growing wheat in Kansas (don´t ask, I don´t know), gay romance manga featuring guys so thin they might as well be made of Popsicle sticks, or the Oscars every year (and the Golden Globes too) even though she hasn´t watched a new movie in a decade, and a movie that didn´t involve superheroes in even longer, and *I* can´t make any sense out of it. Boomers, man, idk.

¨I got to pretend, for a few long hours of a deeply boring television broadcast, that I was a real person, that I’d managed to do it, that I had built myself a home in the world, just like everybody else.¨

Where´s the essay on you being a character in a Edvard Munch painting?

elm

i´m curious