There are two things that happen on sitcoms that fill me with a wild and unquenchable longing. One is any time anyone orders, and then receives, a pizza, and the other is Friendsgiving.

I don’t know that I can — or even should— try to explain the longing for a pizza that rises, monstrous, in me when a pizza arrives on screen in a television show. If you don’t instantly seize up with incapacitating desire, with the same kind of want that frequently when I was younger caused me to ruin my life over terrible people, when you see a pizza box heavy with wet cheesy warmth land on a kitchen table, then we are fundamentally different people. The pizza is the whole thing of desire. Wanting someone very badly, someone who is very bad for me, feels like wanting a pizza, and not the other way around. Wanting success, or safety, or people who have hurt me to fail, wanting to be loved or understood or to get some long-shot thing I’ve applied for, wanting all my worries to quiet and finally be proved wrong, wanting to come in from the cold, wanting people who think poorly of me to read something I wrote and be grudgingly moved by it, wanting to sleep when I haven’t slept in a long time, and wanting to be beautiful on the days when I feel the ugliest: all of this feels like wanting a pizza.

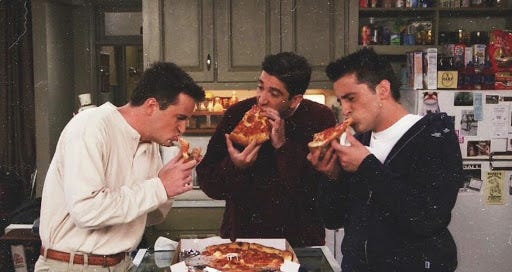

When a pizza arrives on screen in a sitcom, somebody opens the pizza box and one of two things happens: Everyone exclaims in delight (me too, buddies) or nobody reacts at all. Pizza, like those white paper Chinese takeout cartons that were promised to me as a preteen when I watched sitcoms set in New York and then, it turned out, barely existed anymore when I got here, is more often than not just a backdrop, a prop for characters while they talk about something else. The scene is never about the pizza, although to me it always is. But mostly the people on screen take the pizza for granted, even while eating it. That’s part of the longing, the idea that a whole pizza means having so much that you don’t even think about the fact that you have it. What I feel when I see a pizza onscreen is partly the desire to take a good thing for granted, to have so much that I could shrug at having it, carrying on conversation blithely amidst the smell of steam and cheese.

Thanksgiving is a holiday about abundance, which is the first way you know it’s a corrupt and perhaps unsalvageable American tradition. The table is meant to groan under the weight of more food than the people assembled can possibly eat. The idea of shoving as much family as possible into one room, as Thanksgiving is meant to work in the most traditional American sense, is about that same bragging abundance, look how much I have, look how many we are. Any festival of abundance is about taking things for granted. It’s grabbing a slice of pizza from the box without even pausing in conversation, and it’s filling a Thanksgiving table with a double-digit number of dishes, piling the fridge with leftovers after. That abundance is the exact opposite of the out-in-the-cold-looking-in feeling I feel when I see a pizza on TV. Pizza, and Thanksgiving, are the place behind the glowing-warm windows that beckon to those of us out in the cold, and slam shut in the same gesture. The pizza, just like Thanksgiving, is the room on the inside, where it is always warm.

The Thanksgivings I long for the most, in the pizza-box way, are Friendsgivings. Friendsgiving is what it sounds like: A Thanksgiving with friends instead of family. Whether people at a Friendsgiving are absent from their families because of estrangement, or simply because of logistics (travel, money, work), Friendsgiving becomes a holiday about chosen family, subverting the traditional theme of the holiday by allowing friends to stand in for parents and siblings and uncles and cousins and grandparents. In the ideal, these chosen families heal the wounds that real families make. Friendsgiving offers another way to come in from the cold.

Pizza boxes show up in almost every television show set after 1980— I remember once being rendered wholly incapable of paying attention to some high stakes espionage-and-heartbreak plot line on The Americans because Keri Russell had walked into the house with a pizza box— and so do Thanksgivings, and Friendsgivings. But the shows with which I most closely associate pizza boxes and Friendsgiving are Friends and How I Met Your Mother, two execrable pieces of television that I have passively watched enough of to know more about them than I do about other media properties that I supposedly love in some foundational way. There are so many other things I am actually proud to have watched, things I love with my whole best heart, all of which I think about far less than I think about Friends, a TV show I actively do not like.

Friendsgiving is the backbone of these shows. Essentially they are both shows about Friendsgiving, and essentially they both take place on Friendsgiving in every episode, not just the actual Thanksgiving ones, which are only sometimes Friendsgivings. Friendsgiving-type sitcoms such Friends and How I Met Your Mother are shows about loneliness because they are fantasies of a world in which loneliness is not possible. Ted (a piece of shit, the worst man) spends seven seasons of How I Met Your Mother trying to find The One, the woman he dreams of marrying. That’s the premise of the show. But he’s never actually lonely; he’s just dissatisfied. He always has someone to go home to, a riotous and enveloping group of someones, and most of them actually live in his apartment, or will somehow be in his apartment when he gets home, even if they don’t actually live there. The Friends friend group goes through I believe seven divorces among the six of them over the course of a ten season run. These experiences, and any other griefs suffered, manifest as sadness, whininess, anger, and frustration, but never actual loneliness, because the premise of shows like these is that with the proper type of big-city friend-family, there is no human experience that can ever cause you to be lonely. Disasters, hurts, divorces, breakups, arguments, betrayals, even deaths, are all merely ways for your friends to be there for you. The point of any painful event in these characters’ lives is not to show that it is painful or how the pain affects them, but to show how the friend group reacts to and rallies around it. All of your grief is an opportunity for you to be better loved by the community that waits at home in your apartment; nothing can happen to you that can isolate you. There are no hurts that you have to bear alone, and no experience bad enough to cause you to be lonely.

Grief does not work like this, in my limited experience of it. I think everyone probably knows this; I think I knew this before I had either experienced grief or had friends, watching Friends as a lonely teenager home from school in the late afternoon on a Thursday. At times I have been hurt so badly that no one could reach me, and sometimes, as ugly as it is to admit this, my sadness or my anger or any of my other reactions to grief, to loss, to betrayal, has in fact driven my friends away, whether temporarily or forever. Sometimes I’ve been that friend, too, the one who found it too difficult, who meant to respond but didn’t, who couldn’t be there for my friends, who ignored the texts or the phone calls, shut up alone in small rooms, ungenerously tending to my own worries. The abundance fantasy of Friendsgiving is one in which unconditional friendship is always available in wasteful too-muchness, so much love that I could take it for granted forever, talking right through grabbing a piece of pizza, not even reacting as the pizza box arrives.

Pizza on a TV show is that same feeling, a glimpse of an alternate universe in which no one ever has to be lonely. That’s the pizza-box longing, too, the same feeling when I try to order a pizza, or have my friends over on a major holiday, and I mean, I do it, sort of, technically, it does count, but it never feels quite right. The longing can’t ever be sated by just going out and getting the thing— pizza, some friends who will come over to my apartment for a meal— because it isn’t pizza, or Friendsgiving, that I want, but the warm-room sense of always having enough. Pizza boxes and Friendsgivings on television both say that if only you could do this correctly, you would actually be a person. This thing happens over here, where the people who are actually people are, having friends and eating pizza, and never being hungry or alone.

At first, my husband and I thought we were going to make a huge Thanksgiving menu for our two-person Thanksgiving this year. We wanted to perform the big abundance: what if we did all the weird sides we’ve ever wanted to make that don’t go together at all, Calvinball Thanksgiving. Then we gave up on that idea. We couldn’t get excited about it, no matter how much we wanted to. It felt wasteful, and sad, and mostly exhausting. I suggested ordering a pizza, or, like, THREE pizzas?? In my head getting a pizza on Thanksgiving was a nigh-on sexual feeling, not just ordering an unnecessary amount of pizza but ordering that pizza on a day of the year when you are specifically not supposed to do exactly this, when you’re supposed to do the cooking yourself and make a production of it. But when I made the suggestion out loud it fell flat; neither of us was up for it and we couldn’t say why. It didn’t feel like a pizza box, and it maybe felt like the opposite of one.

I’m going to make a mushroom lasagna, the recipe for which you can only find on the internet here, in an ancient Tumblr post by the friend who originally told me about this lasagna (she is absolutely correct that it is, almost bizarrely, a sexy lasagna). The lasagna feels a little bit of a piece with the terrible sitcoms that have infiltrated too much of my emotional life, since it’s from the Dean & Deluca cookbook, and therefore a throwback to an idea of 1990s New York that never really existed in the way I imagine it. Nevertheless, the lasagna is very good, and very involved and labor-intensive in a deeply satisfying way. I recommend using twice as much cheese as is called for; the first time I made it, when it was just barely cool enough to cut a piece, I pulled it from the tray to the plate and the cheese sang up in resilient tacky little cords and I thought I’d done it, I was in the sitcom, I was finally a real person at last, I was finally going to want something and then feel satisfied upon getting it, closing that stubborn circle up to a silent whole. That feeling lasted less than five minutes and then all the spaces and the lacks and clumsiness poured back. But it was a good five minutes and I recommend this lasagna. The recipe is going to tell you to use fresh lasagna noodles but listen, I’m not the queen of england and neither are you and it’s totally fine with boxed dry ones.

reminder that griefbacon is back and you can subscribe to it at the button above or here. for now it’s all free but starting in January a little over half of the posts will be for paid subscribers only, including the archives. if you subscribed previously (hi friends) and want a paid subscription, you’ll need to set up a new one. if you want to subscribe but can’t afford to do so, or know someone in this situation, please email me and we’ll figure something out. if you want give a gift subscription (a great holiday gift, a great any time gift), there’s a button for that right here. xo