Griefbacon is on sale this week! Until April 5th, get one year’s subscription (monthly or weekly) for 40% off! because it’s spring, because I love you, because I want more people to be able to afford to subscribe to this newsletter.

The Duolingo Owl is green, which is a color no owl in real life has ever been. He is small and chipper and possibly flightless; I do not think you ever see him spread his wings and soar across the screen in the app. He does not indicate any relationship to flight at all. He is easily hurt, and nothing is ever good enough for him. The Duolingo owl cannot hear your excuses; he does not make allowances for personal crises, or human flaws. He does not care if you are tired, or sad, or busy, or overjoyed, if you are out of work or have met someone new or lost someone you loved. He only cares whether you can offer your attention to him. The Duolingo owl is a thesis about the ability of people to change, and what it might take for them to do so.

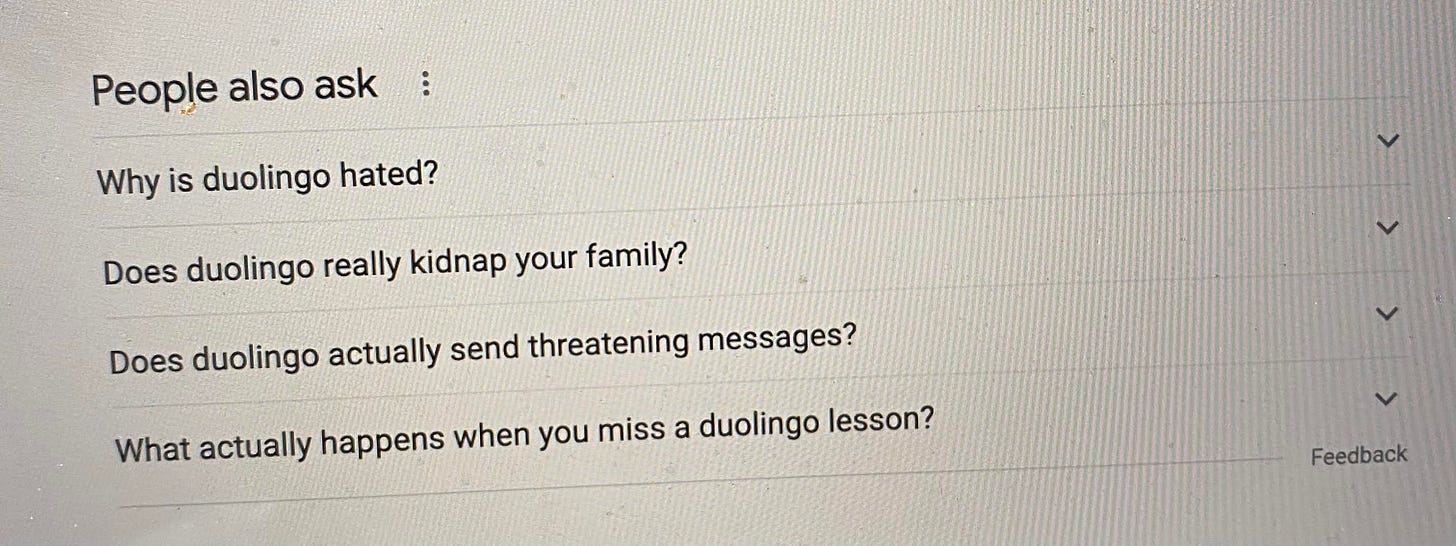

Sometimes pain or shame feels like change, the real, sticky, awful, believable engine of it. Sometimes it’s easy to believe that whatever hurts most is the thing that is going to be most effective. A whole genre of tweet and post and meme exists online about the owl: The Duolingo owl is in your house, the Duolingo owl wants to punish you, the Duolingo owl is emotional violence, the Duolingo owl is straightforward violence, the Duolingo owl will kidnap your family, beg for your life in Spanish. Another raft of these jokes went around during the pandemic, when supposedly even more people, stuck inside with their social lives vastly reduced, were using the app to try to learn a new language. A popular tweet called the owl “the ultimate male manipulator,” and several others proclaimed some version of “no one can make you feel bad about yourself without your permission except the Duolingo owl.”

Most anyone who had ever used Duolingo could relate. These jokes arise from the almost admirably horrible way that the app’s developers have chosen to structure and to write its built-in notifications. Duolingo is a language learning app in which the owl is, ostensibly, your language teacher. He’s an owl because owls are wise; he’s green because of some kind of inside joke at the company apparently; he’s cruel because change and learning are both cruel, and demand pain of those seeking them.

As far as I can tell, the people working on the app have leaned into its nigh-on-absurd level of emotional manipulation because they saw that it was what people were talking about when they talked about Duolingo, meaning it got Duolingo noticed (although the guilt-based appeals may not in fact be all that effective at getting people to use the app). Much of tech and business is like when a middle schooler makes one single successful joke for the first time in their life and then proceeds to tell that joke again and again at increasing volume and to decreasing effect for the next hour, or possibly the next ten years. Emotional terrorism is the thing for which Duolingo is best known.

The app tells you over and over that practicing a short amount a day is the best way to learn a language, and encourages you to keep up a streak. Duo sends you daily reminders to practice the language or languages you’ve chosen. When you miss a few days, you get an email that says “you made Duo sad,” showing a cartoon owl crying large tears. When you stop practicing for a longer period of time, eventually Duo sends you a message that says “these reminders don’t seem to be working. We’ll stop sending them for now,” which is so brutal that the first time I received it I stood still in the middle of a busy street, blinking at my phone. It’s the exact cadence of the parent who is not mad, just disappointed, the soccer coach who knows you could do better if you really tried, the English teacher who just wants to see you succeed , the friends who have to stop talking to you for your own good because they can’t enable this behavior. This emotional knife-twisting is the source of the memes about Duolingo kidnapping your family, and it is Duolingo’s philosophy about what causes people to change.

In Bad News, the second of Edward St. Aubyn’s Patrick Melrose novels, at one point a character thinks to herself, “of course it was wrong to want to change people, but what else could you possibly want to do with them,” which is a thought that the Duolingo owl has definitely also had. The third-person narration in Bad News is meant to viciously mock the characters whose heads it inhabits, taking aim at each individual from within as it leaps between their thoughts. But I remember being guiltily struck by this line when I first read it because it was also how I felt.

When I was young and stupid and terrible, I believed for a while that I could game out people’s reactions to me. I thought I could learn other human beings like a language. I had been extremely socially awkward as a kid, and had somewhat gotten over it, and I very wrongly perceived this as some kind of wizardry, a spectacular skill that meant I could anticipate people’s needs and reactions and twist them so that people would behave how I hoped they would behave. As is the case for most every noxious person who has ever believed they had this skill, it never actually worked. I didn’t succeed at manipulating anyone; I just made them mad at me, and alienated a lot of people whom I would have liked the chance to love. Eventually I learned the same stupid lesson that everyone learns: You cannot in fact change people, nor can you change their reactions to you in any significant way. Mostly no one is thinking about you, and mostly everyone is going to do whatever they were already going to do. Learning this did in fact change me but, like most change, that maturation was not born out of wizardry or manipulation. Rather, it was born out of pain over an extended period of time, out of hurting people I loved, and losing people I cared for. I began to change when I began to understand the ways in which I was often the villain in the story, my own and other people’s.

There’s a scene from Angels in America that’s been stuck in my head ever since the first time I read it many years ago. Harper, a woman at the rock-bottom of an emotional crisis, visits the Mormon Church’s Visitor Center in Manhattan, and, in a dream sequence that is maybe also a drug-fueled hallucination, imagines that the diorama about a Mormon family’s journey across America comes to life and speaks to her. Harper and the diorama figure of the Mormon mother engage in the following dialogue:

Harper: In your experience of the world. How do people change?

Mormon Mother: Well, it is has something to do with God, so it’s not very nice.

God splits the skin with a jagged thumbnail from throat to belly, and then plunges a huge filthy hand in, he grabs hold of your bloody tubes and they slip to evade his grasp but he squeezes hard, he insists, he pulls and pulls til all your innards are yanked out and the pain! We can’t even talk about that. And then he stuffs them back, dirty, tangled, and torn. It’s up to you to do the stitching.

Harper: And then get up. And walk around.

Mormon Mother: Just mangled guts pretending.

Harper: That’s how people change.

A lot of the time this is my understanding of change: A process that is always painful, one that necessitates destruction and sacrifice. No one wants to change in the same way no one wants to be uncomfortable, or do anything unpleasant, but discomfort and unpleasantness are almost always hallmarks of the kind of changes people want to make, not just the large and noble ones, but even the small and selfish ones too. Being a better person, having a better life, loving others or being more able to be loved by them, being more attractive or more successful, becoming kinder, getting better at a skill, or speaking another language: All of these necessitate discomfort, some sort of trial by fire. Moving beyond ourselves, our well-worn default paths, is rarely possible in a way that is not excruciating. All the ways in which I have ever legitimately changed have been borne out of loss and discomfort, doing things I would never have chosen to do if the choice had been available.

In this way, the tiny green owl, with his cheery flightless expressions and his big blue tears and his passive-aggressive texts and his commitment to shame and cruelty, seems share Angels in America’s ideas about how people change. Perhaps the Duolingo owl sees right to the accurate heart of what it would take to do something as large as gain fluency in another language and therefore become, in the way that language in particular makes possible, a wholly different person, slipping out of the bonds and strictures of my narrow and pre-made life.

The Duolingo owl believes in cruelty, but he also believes in the slow miracles, the small and invisible work of each day piled on the next. Duolingo makes the promise that if you do a small thing over and over again, it will yield abundances, a bird chipping away at a mountain year after year. It is the same old gospel that well-meaning parents and middle school teachers and sports coaches preach: A little bit of work every day, adding up eventually to great and mighty transformations. At its best, this is the way I would like to believe change works: Not the thunderbolt that splits the body in two, but the silent early morning, sitting at a desk, showing up to the gym, walking out to the basketball court in awkward legs and old sneakers before anyone else is awake, doing something badly for long enough that one day I can do it well. There are many reasons I am perpetually sad that I don’t play sports seriously, but a central one is that I want a proof of this kind of change to carry around, an assurance based on feet and limbs and breathing, slow mornings and sudden miracles and doing it again. I want something to tell me that sometimes change is boring, and undramatic, and happens just the same, a slow and certain tide, a thing that can be believed in, the light that comes back into the world.

But then there is the fundamental fact that Duolingo quite simply does not work. If you would like to be more polite on a vacation, better able to navigate your way around an unfamiliar city, or better equipped to order in a restaurant there, Duolingo provides a genuine utility. But no matter how many days I can go without making the owl cry, Duo is not really teaching me French, because speaking another language is something one learns socially, and out of desperation, in the same way that desperate circumstance and necessity is the only thing that makes people brave, or kind, or makes them change. Everyone I know who has ever seriously learned a language, to the degree of fluency that encompasses charm and jokes and sarcasm and argument and work and negotiation and love, has learned it because they were in one way or another forced to do so through a process of social humiliation. In the month before the world shut down, my mom and I were in France together, and I promised her I would only speak French with her in public. She is fluent and I am very much not. I speak enough French to be good at French Duolingo which is to say, almost none. One night I spoke my terrible Duolingo French to her through the entirety of our dinner at a small and overcrowded restaurant. Every sentence was stuttering and terrible, a total joke, and yet I felt proud of myself and this one humiliating dinner in a way that I have rarely felt about anything I have ever done with great fluency or ease.

The thing about Duolingo that replicates the real process of learning a language, then, is not the kindly-soccer-coach aspect that promotes the small and accumulated daily doing of a task, but rather the outlandish cruelty that inspires memes. Perhaps Duolingo the emotional manipulator is artificially recreating what it would feel like to get laughed at by French people every day all day for a year and fail to make friends because the skills I learned as a child in English are unavailable to me as an adult in French. Perhaps Duolingo is allowing me to experience walking home each day in a foreign country defeated and lonely, as though the house of cards of my identity were knocked down and I had to start over, building a self upwards from the ground floor. In this way, getting repeatedly shamed by a green cartoon owl is just an expression of how change happens, a series of daily humiliations, and then, maybe, if we’re lucky, a rebuilding and reemergence. Perhaps both can be true at once, the slow accumulation and the lighting bolt, the early morning basketball court, and the mangled guts pretending.

Years ago, I watched an owl hunting prey, way out in a big summer nowhere, in middle of the night. I was walking with a group of other people from where we had had dinner back to the campsite where we were staying, a path that went through a long unbroken darkness in the woods. Right as we approached the clearing at the top of a hill, an owl swooped in a few feet from us at the side of the path, going after a rodent in the underbrush. There was an enormous rush of wings; I didn’t know that it was an animal rather than weather until I saw its eyes flash. It was beautiful and terrible, murder and freedom, a sinister blessing out of an ancient darkness. I realized I had never seen an owl with its wings spread except from very far away, and I had never before seen one move fast. It moved with ruthless and unforgiving efficiency, silence and nothing and then majesty and death and awe and then silence again. Sometimes change is like that, too.

Sometimes change is neither slow work nor painful humiliation, but an unstoppable and uncaring force, uninterested in our silly little efforts. As this year has demonstrated loudly and as every year demonstrates quietly, far more often than it is anything any one of us can effect personally by our actions, change is something that happens to us, in all the horrorshow of luck and the inexorable tide of time passing, the bad weather swooping across the landscape where all we can do is stare, powerless to stop it, swept up in the grasp of something too large to comprehend.

thanks for reading. this is the weekly public edition of griefbacon. if you enjoyed this, maybe consider subscribing? griefbacon is on sale this week, so it’s a great time to do so. subscribing gets you access to the weekly discussion threads (which are a weird and kind and wonderful secret online space) and the additional weekly subscriber-only essay on the weekends. you can also check out the archives here to see what this is all about. if you’d like to subscribe but can’t afford to do so, you can always email me and we’ll figure it out. xo

You make me want to be a better writer.

Quoting "Friends" is embarrassing but I still say "nobody likes change" and in my head it's always;

Ross : ... no, I-, no I wanna stay, I wanna talk about this.

Rachel : Okay! (slams the door shut) Alright. How was she?

Chandler : Uh-oh. (as Phoebe, Chandler, Joey and Monica listen with their ears to the door)

Ross : (exhales shortly) What?

Rachel : Was she good?

Joey : (as if coaching Ross) Don't answer *that*.

Rachel : C'mon, Ross, you said you wanted to talk about it, let's talk about it! How was she?

Ross : She was ...

Joey : (as if supplying him with possible answers) ... awful ...

Chandler : She was not good ...

Joey : ... horrible ...

Chandler : ... not good, not good!

Joey : ... nothing compared to you.

Ross : She (exhales, frustrated) ... she was different.

Joey : (like someone watching a game show) Ooooo.

Chandler : Uh-oh.

Rachel : (icy) "Good" different?

Ross : Nobody likes change ...