Everything I've Binge-Watched in the Last However Long, Part One of Two

high school is about horror, westerns are about the internet, parties are about loneliness, tenet is about not very much at all and that's grand

Hello, hi, happy Monday I guess. This post is part of an ongoing series in this newsletter. Some earlier pieces are here, here, and here. There are also a whole lot more than that, these are just a few examples. Since I haven’t done one of these in a little while, this entry (and its second half) cover quite a bit of ground, so all the selections may not be exactly of the present moment. I think that makes it fun; your mileage may vary.

Anyway, I’ve binge-watched some stuff, for a very broad definition of binge-watched, recently. Maybe you have too. Here are some thoughts on some of it. There’s a part two of this for paid subscribers as well; now’s a great time to sign up for a paid subscription if you want to read that as well.

Yellowjackets, seasons 1 and 2: Whether we ever get over high school is a question that has been answered definitively by the sheer volume of television about it: No.

American media has all but reified the brief and flimsy years of adolescence out of existence, its laser focus on this one small part of life like a microscope over an ant colony on a hot day. No matter how old I get, people my age still compare everything to high school, as though a blight had wiped out all other available metaphors. New York City is high school, the publishing industry is high school, parties are high school, friendship is high school, dating is high school, the internet is high school. Psychology, work, trauma, romance, art— all of it relates back to some thing some teacher or classmate said during a slim four years more than a decade ago. High school recedes ever further into the past, yet never quite fades into the background. Not everyone, by a large margin, goes to high school, and even for the fraction of people who do, the experience is brief, rarely interesting, and not objectively very important. Yet high school keeps crowding into the center of the screen, refusing to cede its outsize portion of the view.

Every generation gets not one high school show, but dozens, from Buffy the Vampire Slayer to My So-Called Life to 90210 to Freak and Geeks to Skins to Euphoria to Stranger Things to Riverdale to Sex Education to Gossip Girl, just to name a tiny fraction of all the shows that have been casting attractive 28-year-olds as high school sophomores since I was old enough to be aware television existed.

I haven’t watched most of these shows, because I’ve spent more than enough time in high school already. I grew up on the campus of a high school where both of my parents worked, and for about a decade after college I supported myself by tutoring high school students. High school was my childhood, and then it was my job; I didn’t need it to be my leisure time. High school is too much with us, late and soon, or at least it was too much with me.

One show that’s always been my exception, however, is Buffy the Vampire Slayer. I’ve seen Yellowjackets called “prestige TV” a lot, which strikes me as a little silly. It seems obvious that its predecessor isn’t Breaking Bad or even Lost, but Buffy, the first television show I ever truly loved. I love Buffy in the way one might love a childhood home or a family member, with an irrational possessiveness and a long-standing over-identification. I like a lot of good, profound, serious, high-brow adult things, but, if I’m honest, I like very few of them as much as I love Buffy the Vampire Slayer, a show I don’t even think holds up all that well, and which is at its absolute pinnacle still grating and uneven. But that’s not how love works; I learned that from watching Buffy.

Buffy’s tagline, and thesis, and organizing principle, was “high school is hell.” Its literal high school was built on top of a literal hellmouth. The metaphor was beyond heavy-handed, but that was part of what made it so bone-deep pleasurable. Yellowjackets is a lot like Buffy in its wobbly turns between serious drama and B-movie spookiness, its folk-horror references and witchy 1990s-feminism, its tangled, lived-in teenage relationships and its use of horror tropes to punctuate heightened moments in those relationships, like the songs in a musical. I suspect that’s part of the nostalgic pull that’s made Yellowjackets so popular with viewers who are the target audience for its first-generation Lilith Fair needle drops. Yellowjackets and Buffy are both goofy takes on horror movies, more spooky than actually scary, more interested in coziness than dread, putting blood and guts and monsters on screen, but using them to talk about the same thing television’s always talking about: found family, and buried trauma, and high school.

Like Buffy, Yellowjackets uses B-movie tropes to make the horrors of adolescence literal. The power struggles, jealousy, boundary-testing and early sexual exploration that signpost adolescence—and, in both cases, specifically female adolescence— are rendered as movie monsters, creaking skeletons, spooky cabins, evil trees, ritual cannibalism, and possible witchcraft or cult magic. Through these outsize elements, the show tells the same small-scale, familiar story about the space between childhood and adulthood. By exaggerating its depiction, it gets right to the heart of the thing in a way purportedly realistic high school shows rarely ever manage.

High school is hell, and so are the years that proceed it. Childhood is brutal, and it’s a wonder anyone survives it at all. But to make that statement is to invite mockery, to take a position impossible to defend in rational terms. Viewed at a distance, much of what typically happens in childhood seems inconsequential compared to what comes next. But pound for pound and ounce for ounce, the pain I’ve felt about any adult problem has rarely, if ever, risen to the level of the pain I felt in fifth and sixth grade, when I briefly and for the first time had friends, and then, for no reason I can even to this day understand, just as quickly didn’t. When adults talk about “socialization” in terms of childhood development, it sounds gentle and scientific, like learning to count or to read. In actuality it’s more like locking a bunch of starving rats in a crate. What happens inside is nasty, and violent, and unspeakable. Children are thrown together, at a time when we have yet to develop kindness, compassion, empathy, or social skills, with the idea that our interactions will produce those things. And, sure, often that’s what happens. We learn that other people are people by living up against them; we learn that they can hurt us and that we can do the same in turn only after we get hurt. Maybe we emerge from childhood with skills, with knowledge, with some of the maturity and some of the social awareness necessary to continue climbing the greased ladder up into adulthood. But many of us do so at an enormous cost, and there’s almost no way to talk about it later that meets the weight of it, the volume of what we carry away from those years.

Were I to try to explain any of this to anyone, now, in my thirties, it would sound stupid. I’ve negotiated on the phone with collection agents and talked through options with hospice nurses. Am I really going to sit here and tell you that other children saying mean things about me before I was old enough to vote or drink was as bad as any of that? The thing is, I am. I had nothing else to fall back on; there was nothing else there yet. Bad things happen now, but other things do, too; there’s always somewhere else to go. As a kid, it wasn’t just that other kids were mean to me; it was that their meanness was the whole cumulative sum of my existence. The skin of the world was so thin that any single cruelty punched a hole right through the backdrop that looked like the sky.

For some people the thing that happens in childhood isn’t other kids, but their own family, or a tragedy that cuts that family apart, or loss, or illness, or grief, or the cruelty of our society’s ever-present systems. It’s certainly possible to experience much larger traumas in childhood than social exclusion or bullying. The point is, at that age, any and all of it is the same size, which is the size of everything. Each new memory represents a mathematically significant percentage of our entire lives. Whatever happens in childhood becomes, for a while, the only thing that’s ever happened. Whatever wounds us at a young age reshapes us in its image, all of it a high-stakes high-contact sport which we’re told we’ll learn how to play by playing. By the time we get into our twenties, we’re all zombie rats, emerging from the crate when it opens again, lumbering up into daylight blood-stained, pretending not to be monsters.

Even now, trying to talk about childhood, I’ve ended up at a grisly metaphor: Zombie rats in a box, eating one another. The disconnect between what childhood looks like and how it feels can make realistic depictions frustrating. Adding in the portals and the blood and the gore, the fangs and the jump scares and the guys in overdone VFX makeup, makes high school more recognizable than a technically accurate reproduction. “Sometimes you can lie and be truer than the truth,” said Tim O’Brien in a book I remember perfectly two decades later because I had to read it in eighth grade. He was talking about the Vietnam War, but he happens to also be right about TV shows where high school students turn into werewolves and cannibal antler queens. Flannery O’Connor wrote “anyone who has survived his childhood has enough information about life to last him the rest of his days,” but when I try to explain what I survived— children saying mean things? sitting alone at lunch?— it sounds like nothing at all. Turn it into a vampire, a demon, a plane crash in a possibly haunted forest, and it finally makes sense; turn high school into a horror movie and it finally feels possible to talk about high school.

Anyway, this makes Yellowjackets sound a lot more serious than it is; it’s this serious maybe a third of the time and when it is it’s very good, but, in the grand tradition of Buffy, it’s extremely silly, too. If you haven’t watched any of it, and if this description sounds the least bit appealing to you at all, I cannot recommend enough starting it right now. The first season is god’s own perfect binge-watch, like the platonic ideal form of what to do across the length of a rainy Saturday indoors. The second season isn’t as good as the first season, but that’s ok. I’m not sure if the writers know where they’re going with this, and if they do I’m not sure it’s going to satisfy anybody, but that’s the nature of almost any mystery-based anything; outside of a few spectacular exceptions, a mystery necessarily gets less interesting the more answers one learns. Elijah Wood is on Yellowjackets and it’s the most I’ve ever liked him in anything. Please give Juliette Lewis one million roles for which she can win awards, please somebody cast Juliette Lewis in a PJ Harvey biopic, like, yesterday. I’ve always liked Melanie Lynskey but now I would follow her into hell. I don’t know anything about horror as a genre beyond having Emily’s number in my phone, but I’m pretty sure one of the four or five building-block stories in horror is “we think we know our parents but we don’t,” and Melanie Lynskey is basically playing this concept in a passion play here, and she’s doing an amazing job.

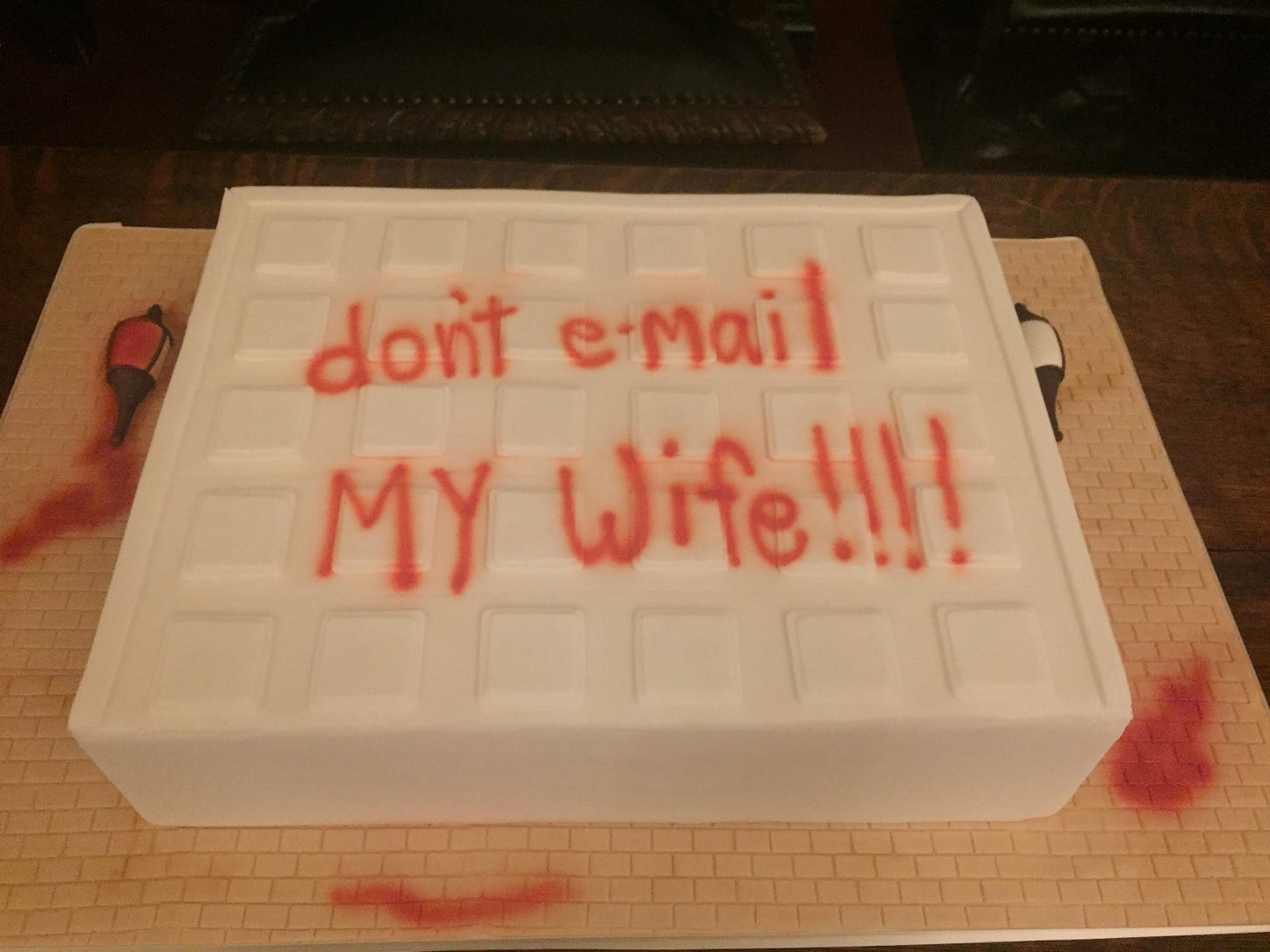

Probably you’ve heard about the music on Yellowjackets but every needle drop is perfect and my reaction to each one is a more precise document of my exact age than my birth certificate. I hope Tori Amos is having a good day today. You won’t be surprised to know that some of the music is off of Hole’s Live Through This, but there aren’t enough songs off of Live Through This, which is to say the show hasn’t yet used every single song off of Live Through This. Anyway, our culture as a whole has still not sufficiently apologized to Courtney Love, or sufficiently acknowledged how perfect an album Live Through This is. Lauren Ambrose is on this show and I’ve been in love with Lauren Ambrose since the moment she walked on screen for the first time on Six Feet Under and I’ll be in love with Lauren Ambrose until the day they put me in the ground. The show has almost too good of a time with its secondary characters, and Shauna’s husband Jeff is like if the “don’t email my wife” groom’s cake I had at my wedding gained sentience and became a human man. I have a lot of other stuff to say but all of it is spoilers. I actually think I would be pretty good at surviving in the woods but I would also be very annoying.

McCabe and Mrs Miller: A few months ago, a bank failed in America, and that’s what this movie’s about. The bank that failed was a bank for start-ups. The country we live in is an infinitely deep nesting doll of start-ups, all of which eventually fail, all of whose most viable product, in the end, is the dream of making another start-up. That’s what this movie’s about, too.

Over the hill, you can see the ocean in the distance, but you only notice it when the train comes over the hill, and then you don’t notice it, because you’re too busy noticing who’s on the train. When the town catches on fire, you find out who the mayor is; there’s always a mayor, even if you don’t know there’s a mayor. You think Warren Beatty’s a cowboy, and it turns out he’s just a guy in a cowboy costume, which is also what happened with the bank, and in most westerns, and most stories about America that think they’re origin stories. When people use the word “infrastructure,” they’re almost always using it as a euphemism for something that has little or nothing to do with infrastructure. A society spreads over a map like kudzu, and words like infrastructure begin to function the way words do in religion rather than in dictionaries, as code rather than as meaning. That’s what this movie’s about, too: It’s a movie about infrastructure.

All westerns are movies about infrastructure, and Altman calling his western, accurately, an “anti-western” doesn’t make it any less of a western. Most westerns are about infrastructure in that they depict the dangers and possibilities that exist in its absence; Altman’s movie is about what happens when infrastructure arrives, and arrives, and arrives again, when the wilderness becomes the town, and how capital in all its codes and systems encroaches like a virus. All American society is, or ever was, is people trying to use one another’s bodies to climb up higher than the body next to them. All of this is what makes the movie a western, more than a tense shoot-out at the end or sex workers wearing lacy dresses while saying dirty words. All westerns, although most of them had no way of knowing it when they were made, are about the internet. Released in 1971, when the world wide web was distant science fiction to the vast majority of the population, McCabe and Mrs Miller is, for my money, the best movie ever made about the internet; it has as much in common with Hackers or The Matrix as it does with Butch Cassidy. That’s a longer essay, though; maybe one day I’ll get around to it.

Anyway, I’m not going to tell you why this is one of the greatest movies ever made; approximately one million people have already written better and deeper pieces than I ever can on that fact. What will tell you is that I’d seen this movie a few times a long time ago, but I saw it again in February and it’s on this list because I’m still thinking about it today and have been thinking about it since, not just because it’s beautiful or important, which it is, but because it’s such a good time. Like all of Altman’s films, no matter how bleak their subject matter, it’s first and foremost a great hang. What it has to say about American society is brutal, but how it delivers that message is almost obscenely pleasurable. If it’s a chilly night in the city where you live and a theater is showing this movie on the big screen and part of you thinks oh but I’m tired and in a bad mood and don’t feel great, you should still put on an outfit and leave your house and go sit in the overdecorated auditorium with the self-consciously uncomfortable seats where it’s always the wrong temperature, in the sea of too-small-beanie weekend warriors explaining the movie to their dates, and even if afterwards there’s a track fire at the nearest subway station and it takes you three hours to get home it’ll still feel like you had a great night. The Leonard Cohen soundtrack is so good it’s probably why, several months later, I got so resentful about the boygenius Leonard Cohen track that it made me unable to enjoy their record at all, which was unfair but also I’m still not over it. When Warren Beatty yells I GOT POETRY IN ME that’s me every time I try to send one (1) email.

Tenet: In advance of Oppenheimer (Barbieheimer), I’ve been rewatching, and in some cases watching for the first time, a bunch of Nolan movies. People got mad about this one, and I don’t really get why they did. I liked it a lot, and it couldn’t be less serious if it tried; the fun I had watching it was pretty much exactly the same as when I used to watch an old friend who was incredibly good at video games play all the way through Mass Effect or Uncharted on a long Sunday afternoon. I don’t understand why people are like “oh no I couldn’t follow the plot of this movie” when obviously the plot of the movie is that Christopher Nolan knows that in your heart you have always wanted to do shrooms with Robert Pattinson and he is doing his best to allow you to have that experience in this lifetime. People are like “but I don’t know what happened in Tenet” when clearly what happened in Tenet is that you got to do shrooms with Robert Pattinson, and Elizabeth Debicki was there and was tall, and I’m unclear how anybody wants more than that from the plot of a movie where people have fights on yachts and stuff explodes backwards.

That! Feels! Good! Jessie Ware: My dad went to all the cool clubs in New York in the 1970s, the famous ones, the ones that now stand in for the whole idea of cool. Friends ten or fifteen years older than me went to the dance parties and sex dungeons in Meatpacking in the 1990s, the last time New York was ever a good time. I get jealous and then I remember that I did this stuff, too, or a version of it, and someone younger than me might feel the same way about whatever parties I went to once. The last time that was ever a good time gets more recent depending on how young you are, depending on what you just barely missed. The generation younger than mine has that born-too-late longing for the places where I broke my phone and destroyed my feet as a painfully young person in the early 2000s. You’ve been to a party, we’ve all been to a party; it’s just that a party so rarely feels like a party at all.

It’s not necessarily that the parties were always better before you were old enough to go to parties; it’s that a party is something that only happens to other people. Aaron and I used to talk, joking but not joking, about The Sex, which is the perfect and effortless and always hot sex only other people have. When I have sex, it’s human and fraught and imperfect, part of everything else in my life, mired in the same anxieties and disconnects that touch every other experience. When other people have sex, it’s just hot, free of all this grime and distraction. I might have sex, but I’ll never have The Sex; I might go to a party, but I’ll never really go to a party. All of that’s stuff that only other people do.

That! Feels! Good! is an album about The Sex, and That! Feels! Good! is a party, but what really makes it such a transcendently infectious work of disco is that That! Feels! Good!, for all its pearls and fake eyelashes, for all its purring and posing and growling and glitter, is fueled by the fear that a good time only happens to other people. Like all great pop music, it’s lonely, even at the beating heart of a hot bright room. It’s dancing as fast as it can to get away from its loneliness, hoping it’ll evaporate if the room gets sweaty enough. It’s tempting to think that happiness is easy for everybody else. But happiness is almost never easy for anybody; if it were, we wouldn’t have to get all dressed up and put ourselves in a sweaty room about it.

Ware’s ecstatic, oil-slick, sweat-down-the-walls album is a party about not being invited to the party, a love song about not being loved. The lyrics don’t say any of this; the words are as glossy as the music behind them. It’s that they say the opposite so hard that the desperation peeks through; no one who has to talk this much about having a good time has ever found having a good time to be easy. No matter how glam, no matter how ecstatic, the album is dancing despite something, not because of it. I can retell stories of nights out downtown in the 2000s, sprinkled with indie-sleaze-recognizable nouns. I can make those stories sound gilded and funny, as though they happened to someone else. I did have a lot of fun, but the fun was always despite, not because. Disco is always hard-won. It’s joy snatched from the jaws of everything around it that makes an overwhelming argument against joy.

Ware’s album is pure pop sugar, the lipgloss haze at the end of the view on a hot day, the smell of gasoline on pavement, a bikini as clothes, a party where sweat beads on the walls, a glittered-up eyeliner-heavy couple making out on the subway train home. It’s a good time and it’s a party and none of it is easy. The music is muscular and athletic; the dance beats are try-hard fun and white-knuckled joy. It’s grand and lonely and sexed-up and joyful and furious and kind, too-big fake eyelashes and too-high heels and too-heavy makeup and the cracks that show in that makeup on a humid day, when the beat kicks in, when the drums get going. Sweat cuts through the glamour, and shows that glamour is hard work, every muscle in a body straining toward joy, trying to make it look carefree. In the spinning room, in the cheering crowd, in the glittered-up disco, at the party that only ever happens to someone else, we all raise our arms in the air and make a joyful noise about nothing at all.

That! Feels! Good! is an embarrassing title, with its three explanation points, but by the same token it’s also a defiant gesture. Sometimes something really does feel so good that you want put an explanation point at the end of every word like a big sloppy kiss. Sometimes a good time really is a good time. Nobody is ever too old to be young, and nobody is ever smart enough to know better, and the party isn’t over even if it isn’t easy. We’re all nervous and lonely and trying too hard. We put on eyelashes and wigs and makeup and pearls and big shoes about it, willing ourselves into beauty, and joy, and ease, white-knuckling our way through the party until it finally feels like a party.

thanks for reading. this is the public edition of griefbacon. if you enjoyed this, maybe consider subscribing to the paid version, where you can read the second half of this binge-watch round-up post, or maybe consider recommending a subscription to a friend. subscriptions are sale for the rest of the month, so now’s a great time. xo

I don’t even know where to begin with what I like about this one (which is everything), other than if I start at the end and work my way up, then I get to say how the Jessie Ware album is kind of a Godsend for me? Almost always, I have those go-to albums, the ones I will put on when I open up Spotify and have to pick something anything to give me a soundtrack for the commute or to get work done. But for the last few months, Jessie Ware has been a solid yes without question. T!F!G! is just wall to wall, no skips, revelatory goodness.

I'm really sorry to be this person just it's also glaring to me, I totally get what you're saying and your right but Supernatural is not Remotely a High School Show. Like Sam is in college when the show starts and they are both in their 20s? I know this seems nitpicky and it totally is.